Eli "Peck" leBlanc Witnesses Rum Running in Ecorse

The Detroit Evening News recorded an instance where the Detroit River helped sober someone up, the exact opposite of what happened on the River in the rum running days of the 1920s and 1930s. The Evening News reported that Albert Latour was soused in the River yesterday off Belle Island, and it sobered him right off. When nearby boaters picked him up, he told that he had ‘shadows flitting around him.” The only shadow his rescuers found was a whiskey bottle nearly emptied. They picked up him and his skiff and took them to Belle Island.

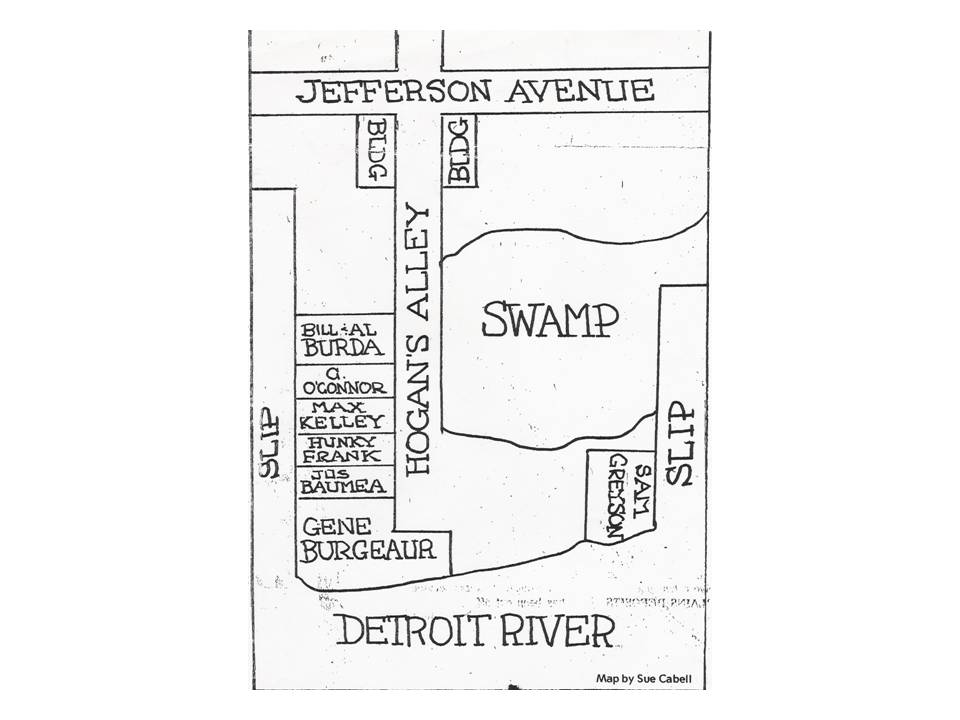

During the 1920s and 1930s the Ecorse waterfront especially near Jefferson and Southfield and a strip of river front called Hogan’s Alley became notorious for its nightclubs. Gambling, bootlegging and other nefarious activities took place on the Ecorse Waterfront and bandits and gamblers from Detroit routinely traveled to Ecorse to ply their trades and hide out from the police.

In 1920, Albert M. Jaeger had become the first salaried fire chief in Ecorse and with a force of three men, took up office in the wooden city hall across from his house. At age 57 in 1945, he went to his office at the fire department in the new municipal building to receive the hearty congratulations of the 28-member fire department.

About 1922, two years after he was installed as Ecorse’s first fire chief, Village President Fred Bouchard made Jaeger acting chief of police. He held the two offices jointly until 1926 and his joint chiefship provided material for local jokesters. The story had it that Jaeger always worked bareheaded in his office until a call came demanding his services as one department head or another. Then he would grab the correct hat, jam it on his head, and run out of his office to whatever challenge lay ahead.

Holding the joint office was difficult in the turbulent days of bootlegging and rum running in Ecorse. Several underworld hideouts had sprung up along the riverfront, huddled beside the river below Southfield Road. One of them was known as “Robbers Roost”, and often sheltered notorious lawbreakers. One March day in 1924, Jaeger and one of his men, Benjamin Montie, a fire truck driver and auxiliary policemen, went down to Robber’s Roost to investigate a case of petty larceny. Inside the Robber’s Roost, two bandits who had just raided the Commonwealth Bank in Detroit and escaped with $17,000 were counting their money. Chief Jaeger and Benjamin Montie took the men to police headquarters for questioning and then Jaeger, Montie and two deputy sheriffs returned to Robber’s Roost where they found two more of the bandit ring in hiding.

The two men jumped out of a window into the river. They swam back to shore and were captured just as two others drove up in a car. They were Bernard Malley, Leo Corbett, Eliza Meade and Tim Murray. Meade and Corbett were in the car and Corbett drew a gun and killed Ecorse Patrolman-fireman Benjamin Montie. Then Chief of Police Jaeger drew his gun and killed Corbett.

During the scuffle, Meade drove away in the car and a statewide hunt failed to find him. Later he was arrested in Arizona and sentenced to 20 to 40 years in Marquette Prison. As the bank robbers attempted to get away, they threw the $17,000 over the streets and waterfront. Spectators did not return their spoils.

Following the family tradition, Eli “Peck” LeBlanc’s generation played an important part in Ecorse history. In a 1966 interview with Ecorse native JoAnn Coman he recalled Prohibition days. According to Eli, Mud Island, which was formed by logs from a nearby sawmill, acted as a screen for an important tunnel constructed by smugglers. This tunnel extended about two blocks inland and was made in such a manner as to allow the boat to travel on the water and still remain below ground. The rum runners then unloaded the liquor in a combination garage-gambling house on Monroe Street.

LeBlanc vividly recalled Hogan’s Alley in Ecorse, a small side street comprised of a row of dimly lighted shacks sometimes used as private bars that were called “blind pigs.” The majority liquor runs ended at Hogan’s Alley, but only smugglers and select guests who knew the pass word were admitted to Hogan’s Alley. Once inside Hogan’s Alley sights to be enjoyed included young men wearing fancy clothes and diamond rings in imitation of Al Capone, piles of money changing hands and countless cocktails disappearing down thirsty throats. Some people called Hogan’ s Alley the toughest territory in the country during Prohibition times.

In continuous stories, Detroit newspapers investigated the Prohibition years in Ecorse. Charles Creinn of the Detroit Times said that Ecorse, formerly a small, peaceful resort area, became a notorious “rum row” and the center of a dangerous, risky, but profitable industry after National Prohibition was passed in 1920. According to Creinn, millions of dollars changed hands at one time in Ecorse and the three banks in the village of less than 10,000 inhabitants did a thriving business. People made fortunes overnight and lost them just as quickly.

Orval L. Girard of the Detroit Times reminisced with one foot propped on a weather-beaten pier on Southfield Dock.

There was nothing but a swamp where the steel works stand. All along the river front customs picket boats cruised day and night in hopes of discovering the rum running operations in Canada.

The Wyandotte Herald joined the story parade, but said that bootleggers let Ecorse citizens go in peace unless they interfered with snuggling operations. “For a number of years following the advent of Volsteadism, 90 percent of the beer and strong liquor reaching Michigan from Canada came by way of Ecorse,” said the Herald. Before Prohibition, a few boat houses and cottages along the river front were used for legitimate purposes, it concluded.

Then during 1918, boat houses once sheltering pleasure craft were converted to storage for liquor and luggers, which were high speed boats that transported good across the river. Summer cottages were turned into gambling houses with a variety of entertainment. Most of these changes were made along a one-half mile stretch of land not more than a city block wide.

Another Detroit News reporter, Martha Torplitz, wrote that Ecorse changed its personality at night because a Canadian regulation required rum boats to be clear of the piers before nightfall. These boats could travel to Canada at random and load and leave when they pleased as along as they were finished before sundown. The fleet would drop down the foreign side of the Detroit River and wait a chance to escape. Sunset shook the fleet from its daytime drowsiness. Trained eyes watched for signals. A red and green lantern indicated “departure an hour from now” while two red ones meant “start at once.”

Often more than fifty boats, from fifty footers to flat busses, smaller power boats and row boats and skiffs waited to escape to Ecorse shores. The escape required skillful navigating because the boats did not have lights and the skippers did not always know who was friend or foe. Sometimes prohibition boats disguised themselves as rum runner and rum runners often turned prohibition agents for an evening. A skipper had to have keenly attuned senses to be able to tell friend from foe on the river after dark.

As soon as a boat touched the dock, hired men began loading the liquor into trucks and cars, a job that required timing, organization and craftiness. Some bootleggers tied cases of beer under the floor boards of trucks and cars and installed liquor holding trays under dashboards and hoods. Their padded interior prevented the bottles from breaking even during the roughest chases and during the washboard ride over highways to Detroit, Toledo, and Chicago. Some wrapped bottles in burlap and hung them from the bottoms of boats for the ride to market and a few enterprising others installed trays below box cars on trains, then wired the numbers of their cars to the buyers waiting at the train’s destination.

Eli “Peck” LeBlanc picked up the narrative again when he said that cash was the only exchange in this crude bootlegging business with extraordinarily high stakes. As long as the Ecorse rum runners were paid, they did not worry about a load being high jacked or lost or misdirected. But if a customer did not pay cash on delivery the consequences could be cold- blooded murder. Or if someone put false labels on the merchandise to get a higher price for cheap liquor and their customers discovered the trick, the deal could end in a rain of bullets. Police and civilians alike routinely fished bullet-riddled bodies out of the Detroit River.

According to Peck, policemen were not always on the right side of the law. Sometimes official eyes were encouraged not to see the bootlegging activities and sometimes the law ignored the bootleggers out of fear for their lives. “It was common knowledge that police officers were bribed and paid off in other ways to keep quiet.”

Ecorse stood wide open for liquor activities besides transferring it. Ecorse was safe for a night on the town. Ladies in evening dresses kicked up their respectable heels on Jefferson Avenue or did the Varsity Drag in buildings that witnessed more decorous activities during the day. If shots punctuated the hours of an evening out, no one looked up from their drinks for shots were ordinary sounds in Ecorse. Anyone could go down Jefferson Avenue day or night to visit roadhouses like The White Tree, Marty Kennedys, The Riverview and Tom R. ___, run by a former policemen. Many people knew Patsy Lowrey’s on Eighth Street with the backroom decorated in western style with sawdust on the floor and a tin-voiced piano echoing through the room. The price across the bar was fifty cents for whiskey an twenty five cents for beer.

Dr. Arthur Payette, another Ecorse pioneer who practiced dentistry in Ecorse for 35 years in his office overlooking Hogan’s Alley, pointed out a different side of bootlegging in Ecorse. Some ordinary citizens as well as professional bootleggers wanted to get rich quick and with the right connections, packaged ingredients for making beer could be acquired for nominal fees. Stills and other needed apparatus could be found in basements of houses concentrated on Goodell Street and some “home breweries” specialized in watering liquor by inserting a syringe through the cork of the bottle, extracting the liquor, and replacing it with water.

Dr. Payette said that for several years the government did not make much of an effort to stop Canadian liquor from coming into the United States and when they did try to enforce the law, the rum runners usually won out. The rum runners would pay any price for a speedboat if it was fast enough to outrun the law. Some of the customers used to complain bitterly about the prices when protection had to be split five ways: local, federal, state, county, and customs. The doctor vividly recalled a state trooper who came to his office for a teeth cleaning. According to Dr. Payette, state trooper G____ was already out to get Ecorse and during the teeth cleaning he managed to work in some comments about the interesting view of Hogan’s Alley and the bootlegging activity in Ecorse. Dr. Payette silently continued cleaning the state trooper’s teeth. “Minding one’s own business was the best policy,” the Doctor said.

The Detroit News continued to publish stories detailed bootlegging operations in “wild west” Ecorse. Journalist F.L. Smith wrote in the Detroit News that “to have seen Ecorse in its palmy days is an unforgettable experience, for no gold camp of the old west presented a more glamorous spectacle. It was a perpetual carnival of drinking, gambling, and assorted vices by night and a frenzied business-like community by day. Silk-shirted bootleggers walked its streets and it was the Mecca for the greedy, the unscrupulous, and the criminal of both sexes. When the police desired to lay their hands on a particularly hard customer, they immediately looked in Ecorse and there they generally found him.”

The “perpetual carnival” began on August 11, 1921, when shipments of beer and liquor from Canada to the United States became lawful. This opened up a glittering world of rum running, roustabouts, and riches for the ordinary people of Ecorse. Immediately, three Ecorse workers took their savings and traveled to Montreal where the sale of liquor was legal. They bought 25 cases of whiskey and drove back to Windsor. Over and over they rowed a small boat back and forth across the river until all of their treasure was ferried to the American side. They posted a lookout for Canadian and American customs officials just in case, but all went well. They sold their liquor in Ecorse and used their profits to finance a second and third trip. Multiply these enterprises by thousands and you have some idea of the volume of rum running across the river. Both Canadians and Americans with their secret caches of beer and liquor waited “like Indians” among the trees and tall grasses on the Canadian side of the river. Boatloads of smugglers would glide across the river, signaling with pocket torches. A blue light flashed once and then twice – “all was clear.” A large sheet hung on a clothesline meant – “turn back immediately, police arrived.”

Rum running boats by the dozen were moored each day at the Ecorse municipal dock at the foot of State Street (now Southfield), which ran through the village’s central business district. Rumrunners transferred their cargoes to waiting cars and trucks, while residents, police and officials watched. Officials erected a board fence to protect the waterfront but rumrunners went around or beneath it. Some Canadian breweries set up export docks on the shore just outside of LaSalle, Ontario, which is directly across the Detroit River from Ecorse. Fighting Island, situated in the middle of the river between Ecorse and LaSalle conveniently hid rumrunners from police patrols.

Rum running was ageless in Ecorse. Ecorse rumrunners employed as many as 25 schoolboys as spies, lookouts and messengers. In 1922, police arrested a 15-year-old boy delivering a truckload of liquor to a Downriver roadhouse. The boy said that he was only one of several local boys working for the rumrunners. He insisted that he worked only on weekends and nights so he would not miss school. These 13 to 16 year old boys made such good lookouts that the police could not make unannounced raids on blind pigs and boathouse storage centers in Ecorse. The lookout boys usually spotted the police long before they arrived. One state police officer complained that “they spread out along the waterfront and are very awake and diligent.”

Federal and state officials also had a difficult time making rum running arrests stick in Ecorse because the local police were in sympathy if not cahoots with the rum runners. Rumrunners served on juries and the only cases from Ecorse tried successfully were the ones tried in federal courts.

Another Wild West style battle between law and order and the rumrunners and their defenders took place in 1928 in Hogan’s Alley in Ecorse. Several cars and three boats holding about 30 Customs Border Patrol inspectors gathered at the end of Hogan’s Alley at the foot of State Street (Southfield) to wait in ambush for the rum runners. Rum running boats pulled up to a nearby pier and the agents rushed them and arrested the seven crewmembers.

As soon as they were arrested, the crew of the boat yelled for help. Rescuers rushed from all around. Over 200 people arrived to stop the agents from leaving with the prisoners. The people attacked the customs agents’ cars. They slashed tires and broke windshields. They pushed other cars across the alley entrance and threw rocks and bottles at the agents. Before the situation became too desperate, the agents banded together, rushed the barricade, and escaped.

John Wozniak of Ecorse is remembered as one of the more honest rumrunners. Wozniak’s early twenties coincided with the early rum running years in Ecorse. He was enterprising enough to form his own navy of twenty-five “sailors” to carry Canadian liquor into America across the Detroit River. Wozniak gave his sailors standing orders to avoid violence. Wozniak’s men did not carry arms and neither did he. When one of his men got caught, Wozniak backed him and his defense and paid the fine if the rumrunner was convicted.

His love of sports ended John Wozniak’s empire. He sponsored a football team and his team became well known in Ecorse, Lincoln Park, Wyandotte and River Rouge. Law enforcement people would come to the games, frequently to identify the rumrunners on Wozniak’s team. In 1928, federal law enforcement officials broke up a large bribery ring and with his protection gone, Wozniak was arrested. At his trial, Wozniak told the judge, “When I was indicted I was through for good. The law was getting too strong. I sold my boats and scuttled the others. I went into the automobile business and have done pretty well.”

In the early rum running days, the atmosphere on the river resembled a 24-hour party. Women participated with men in the bootlegging and the person in the next boat could be a local councilman or the school drama teacher. Boat owners could transport as many as 2,500 cases of liquor each month at a net profit of $25,000 with the owner earning about $10,000. Some rumrunners made 800 percent profit on a load of liquor. The only real perils of the sea that the rumrunners encountered during those first years were losing directions in the middle of the river at night and collisions with other boats.

In the winter the river often froze solid and the rumrunners took advantage of the ice road. They used iceboats, sleds and cars to transport liquor from the Canadian side to Ecorse. Convoys of cars from Canada crossed the ice daily. Cars on the American shore lined up at night and turned on the headlights to provide an illuminated expressway across the ice. A prolonged cold spell in January and February of 1930 produced thick and inviting ice on Upper Lake Erie and the Detroit River.

Hundreds of tire tracks marked the ice trail from the Canadian docks to the American shore. On a February morning in 1930, a Detroit News reporter counted 75 cars leaving the Amherstburg beer docks. He wrote that ten carried Ohio license plates and headed down river for south and east points on the Ohio shore. Others drove to the Canadian side of Grosse Ile. When they arrived on Grosse Ile, the liquor was loaded into camouflaged trucks and driven across the toll bridge to the American mainland.

But most of the cars drove from the Amherstburg docks to Bob-lo Park around the north end of Bob-lo Island. From there the trail headed west to the Livingston Channel. When the Channel was safely reached, the cars drove south for a mile where the trail forked. One trail led to a slip on the lower end of Grosse Ile. The other fork led about two miles further north. As the car drove, the road was about two miles from the upper end of Bob-lo Park to the Grosse Ile slip. Translated time wise, it was about a six-minute ride over the ice.

The dangerous part of the ride was along the Bob-lo Park side, where the ice was tricky. The rumrunners drove as far as they could with two wheels on the shore. The road from the upper end of Bob-lo Island to Grosse Ile was safe and the ice solid. The rumrunners did not try to hide their goods from the law. One of them told the Detroit News that “the law isn’t the thing we fear most. What we are really afraid of is the ice. Anytime it may give way beneath and let one of us through.”

The iceboats were the bane of the Coast Guard cutters because they were fast enough to be phantoms for the pursuers. Iceboats had obvious advantages over cars on frozen Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River. Sail equipped iceboats could speed across the river in 12 minutes or less. Law officers did not have much hope of catching them. The Detroit News summed up the situation: “A gust of flying snow and perhaps now and then a trace of silver canvas in the wind and the boats were gone.”

Both police and rumrunners used their ice imaginations. Rumrunners nailed ski runners to boats and pushed them across Lake St. Clair or towed several behind a car. When the police got too close, the rumrunners cut their boats loose. The federal agents fit a spiked attachment called ice creepers over their shoes. But running with creepers was slow. Some rum runners knowing this, wore ice skates and gracefully skated away.

Then in 1921, the pirates, including a famous one called the Gray Ghost, moved in. Go-betweens called pullers would carry cash across the river to the Canadian export docks for large purchases. Many of the pullers were robbed and killed and their bodies tossed into the river. In 1922, it was a nightly occurrence to find bodies floating in the river near Ecorse. The Gray Ghost was responsible for a few of these bodies, but generally he remained a gentleman pirate and let his victims escape with their lives. The Gray Ghost was the most famous pirate on the river. His official titles included pirate, extortionist, counterfeiter, and friend of the Purple Gang from Detroit. People called him the Gray Ghost because he piloted a gray boat and dressed entirely in gray, including a gray hat and a gray mask. He carried two gray pistols and a gray machine gun. One of his favorite tricks was plundering pullers on the way to Canada. He would intercept them in midstream, using his powerful speedboat to relieve them of their cash.

Once the rumrunners got their liquor across the river from Canada, they could dispose of it in several ways. Some syndicates paid farmers $20,000 or more to store liquor in their barns around Detroit. Others moved in, uninvited, to the docks and storage areas of the wealthy homeowners across the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair. In 1922 alone, at least $35,000 worth of liquor came to Detroit through the 70 miles of river and lakefront stretching from Lake St. Clair to South Rockwood. When the Gray Ghost traveled to Canada for his buying trips, he had a large selection of liquor from which to choose. On the Canadian side of the river, the exporters had rows and rows of liquor docks. They could replenish their stock from 83 breweries and 23 distilleries.

They Gray Ghost continued pirating without too much interference and disposed of his booty among the bootlegging syndicates of Detroit. Then one day he made a fatal error. He purchased a large load of liquor in Canada with a bad check and irritated some prosperous wholesalers. Five of the wholesalers kicked in $1,000 each and hired someone to eliminate the bad check problem. Rumor had it that the gunman worked for the Purple Gang, but the murder of the Gray Ghost was never solved nor was his true identity ever discovered.

Ecorse continued to suffer a bad reputation throughout all of this rum running activity. Delos G. Smith, U.S. District Attorney, characterized Ecorse as one of two black eyes for Detroit.” To prove his point he warned Mayor Bouchard that if he did not enforce some law and order within thirty days he would send in the State Police. The state police conducted a continuous waterfront vigil, powerful enough to cause most of the smugglers and bootleggers to move their business to Lake St. Clair in the north and Lake Erie in the south. But the liquor smugglers had one power point over the police. They had once used the patrol boat, the Alladin as a rum ship without the police ever knowing it.

It took more than four years of hard work and strategy for the police to capture and convict the bootleggers. When Jefferson Avenue was widened in 1929, the shacks along Hogan’s Alley were destroyed and the city bought the thin strip of land by the waterfront for a park.

Then Prohibition was repealed. A stroke of the pen demolished an entire flourishing industry in December 1933. The rumrunners were legalized out of business and Ecorse city officials tore down the fence by the waterfront and created a park.

In 1936, the Ecorse Advertiser, summarized Prohibition and the changing waterfront in Ecorse when it published a lengthy obituary called Requiem for Walter Locke and Rum Row for Walter Locke, a waterfront colleague of Eli “Peck” LeBlanc. Walter Locke and his partner Ned Magee owned a boathouse restaurant at the State Street (now Southfield) dock and from this vantage point they witnessed the scores of men, boys, women and girls creating the Prohibition drama. Locke saw the scattered boathouses on the banks of the river that had been built at the turn of the century for pleasure boating, but had been taken over by a generation of people who worked at night and got rich quickly. Rents for the waterfront shacks escalated from 10 dollars a month to one hundred. He saw smuggling grow in volume and intensity and a class of men rise who gloried in their own skill, strength, and acumen at outwitting the people who sought to enforce the Prohibition law.

Time passed and Locke heard the voices of thirsty Americans demanding whisky and beer grow louder and he saw the profits for handling them climb higher. The price of cheap whiskey arose to one hundred dollars a case- whisky which would eventually fall back to its norm of $24 or $30 a case.

Bootlegging demographics changed as adventurous youngsters and their outboard motor boats displaced the strong men rowing their sturdy boats across the Detroit River. It took the youngsters and their motorboats ten minutes to cover the distance it took a man an hour and forty minutes to row. Then, as cargoes grew bigger, the luggers, with their huge flat bottomed hulls that could hold hundreds of cases of beer and sleek, swift speedboats with more costly cargoes of whisky displaced the motorboats.

Walter watched rum row blossoming at night into a sea of colored lights and music. He watched the half mile south from State Street – now Southfield – to Ecorse Creek become a glittering cabaret center that became known as the “Half Mile of Hell.” The narrow streets were crowded with automobiles from dusk until dawn and people surged on foot from one spot to another in a frenzied search for entertainment. They paid fifty cents a bottle for beer and fifty or seventy-five cents for a glass of whisky. A meal cost them two dollars and they tipped poor entertainers one dollar and thought they were getting their money’s worth.

Walter watched the gambling spots open and thrive in the encouraging atmosphere and witnessed fortunes made and lost on the turn of a wheel or the flip of a card. He saw one poor Ecorse man make $100,000 in a single night and lose $80,000 of it back again within a few days.

Everyone but “the Law” thrived. The uphill battle of “the law” did not change. Walter Locke saw the “Law”, always in clumsier boats than the bootleggers. The out-numbered “Lawmen hung with the tenacity of bulldogs on their quarry”, but better equipment and the sheer force of numbers thwarted their best efforts.

Then Walter Locke watched the fall of rum row on the Detroit River in Ecorse. It did not fall as gradually as it had risen, instead rum roll shattered like a bottle smashed against a brick wall. He watched the river front shacks where millions and millions of dollars worth of illicit liquor had been stored and passed on become disused and abandoned and then razed to their concrete foundations. He watched the narrow, dirt, River Road turn into a broad ribbon of concrete called Jefferson Avenue, and widen yet again almost to his doors. He watched a growing stream of traffic whiz by and drivers not even glancing at famous local history spots.

Walter and Ned sat on the little veranda of their house boat restaurant discussing a Requiem for Rum Row. Goodbye to the fortunes lost when “the Law” raided Rum Row and found the “plant” where the liquor was concealed. Goodbye to the whisky cars that whipped into and out of the secret boat well garages. Goodbye to the shots ringing out in the night and the lifeless bodies on the river shores of the boys who had “taken the night boat to Buffalo.”

Goodbye to the fortunes won in overnight operation and to the desperate chances that were taken with life and liberty to make a “stake. Goodbye to the private operations of the “boys” and hello to the gangsters who muscled in to take the wealthier of the boys on a one-way ride. The jolly fellows who freely spent their money disappeared and tight-lipped gangsters took their places. The uproariousness of the water front turned into a furtive, stealthy fog. Once or twice a “muscler” offered to cut himself into Walter and Ned’s business. Ned would appear the next day with skinned knuckles or maybe his arm in a sling. Nothing else was said or done.

Large scale bribery ruled the day and rum runners and prohibition agents went to jail. Legal exports from Canada stopped and it became more profitable to make beer on the side. Whisky was cut and alky was brewed in alleys by “the Dagoes.” Suddenly Ecorse was “dead” and so was Walter Locke. If he had lived until the next summer, Walter would have watched trees spreading leafy branches over the county park along the former Detroit River rum row where so much whisky had been landed at midnight. Flowers swayed in the breeze where once dancers had swayed to cabaret music and fishermen instead of rumrunners boated on the river. Perhaps, after all, Walter Locke watched and approved.